Some might say Tynron is no village, but a hamlet, a clachan in fact. It has no shop and few facilities. It has a postbox, an old red telephone box and a village hall. The shop finally closed in the seventies and now people shop locally at Penpont or over the hill in Moniaive. The more adventurous go to Thornhill and most people will forage in the supermarkets in Dumfries at least once a month. Without a car you are stuck! The heart has gone from the village with the loss of the school and the shop.

Trades

Willie Wilson calls 1870-1914 the Golden Years of Tynron. The village was lively with all the children. Various tradesmen flourished there, joiners, the shopkeeper, a wheelwright, a blacksmith at Parkhouse and a shoemaker. Many women were lace-makers, dressmakers, milliners, spinners and weavers. In the 1851 census there were:

George Black, his wife and 7 children, blacksmith at Parkhouse.

Alexander Gracie, tailor.

Thomas Smith and 7 children, joiner.

Alexander Fraser, sawyer.

David Wallace, shoemaker.

Janet Muirhead, dressmaker.

Gradually these trades died out, as goods from the cities became widely available. Jimmy Reid, the joiner, was still working in 1938 at Tynron Kirk.

Searching the records it is possible to find out the names of the folk who did these jobs. For instance, the merchants known are:

George Amuligane 1549

William Wishart 1681

John Grierson 1734

William Irving died 1757

Jacob Carruthers 1770

James Williamson died 1826

Robert Hyslop from 1826

another James Williamson 1837-51 at least. Born in Tynron.

William Hyslop died 1865

James Laurie born Durisdeer, 1857 assistant, then 1868-1914. His first wife, Mary Tyre from Macqueston, died in childbirth in 1882 with her sixth child, who survived.

William Wilson 1914-1959

Marion Pollock until it closed

Tanyard

There was a tanyard at Kirkland. There was a newspaper advert for Tynron Tanyard to be let from Whitsun 1806, lately occupied by deceased Mr Kennedy of Kirkland, with a number of pits, large drying sheds, an excellent bark mill and bark loft with utensils for tanning and skinning. There was an abundance of water. (The lead still runs through Kirkland front garden.) Also a large quantity of oak bark and a convenient dwelling house.

Tynron Kirk Whisky

The famous Tynron Kirk Whisky was made for the shop in the second half of the nineteenth century by Laurie, the shopkeeper. It was blended in the churchyard, using bought-in whisky, and used water from the well behind Kirkland Farmhouse. This well is still open. The bonded store was in Kirkland Farmhouse, which still has the iron bars in the window beside the garage.

Laurie had the contract for supplying the Houses of Parliament with whisky.

Wilson

William Andrew McCubbin Wilson was born in 1882 and baptised at Moniaive United Presbyterian. McCubbin was his mother’s name. His early post office career was spent at Keir. Willie Wilson took the whisky business over for a few years with the shop, but gave it up when the Houses of Parliament contract was lost in 1918. It was apparently lost when the quality dropped and competition from big companies overwhelmed this tiny enterprise. Rumour has it that Wilson watered the whisky down so much that they even noticed at Westminster! Parliament then sent a letter of complaint and also pointed out that this was an illegal still. Previously they had turned a blind eye to this.

Wilson then told the MacRaes that he had stopped making the whisky. The MacRaes being temperance approved of this and dropped his rent (or so the story goes). There is a 5 gallon jar (empty!) of Tynron Kirk whisky in Dumfries Museum and another at Maxwelton Museum. Macara was still blending and bottling whisky in Moniaive early this century. A fantastic article about Tynron Kirk Whisky with great detail is in The Whisky Magazine Issue 52 November 2005, “The Forgotten Blend” by Dave McFadzean.

Robert Burns would have tied his pony up outside the shop in the course of his duties as exciseman touring the local parishes in 1789-90. One of his exhausting round trips from Ellisland was Thornhill-Penpont-Tynron-Crossford-Dunscore. One visit to “Tyneron” is recorded in his handwriting at the exhibition at the Robert Burns Centre in Dumfries.

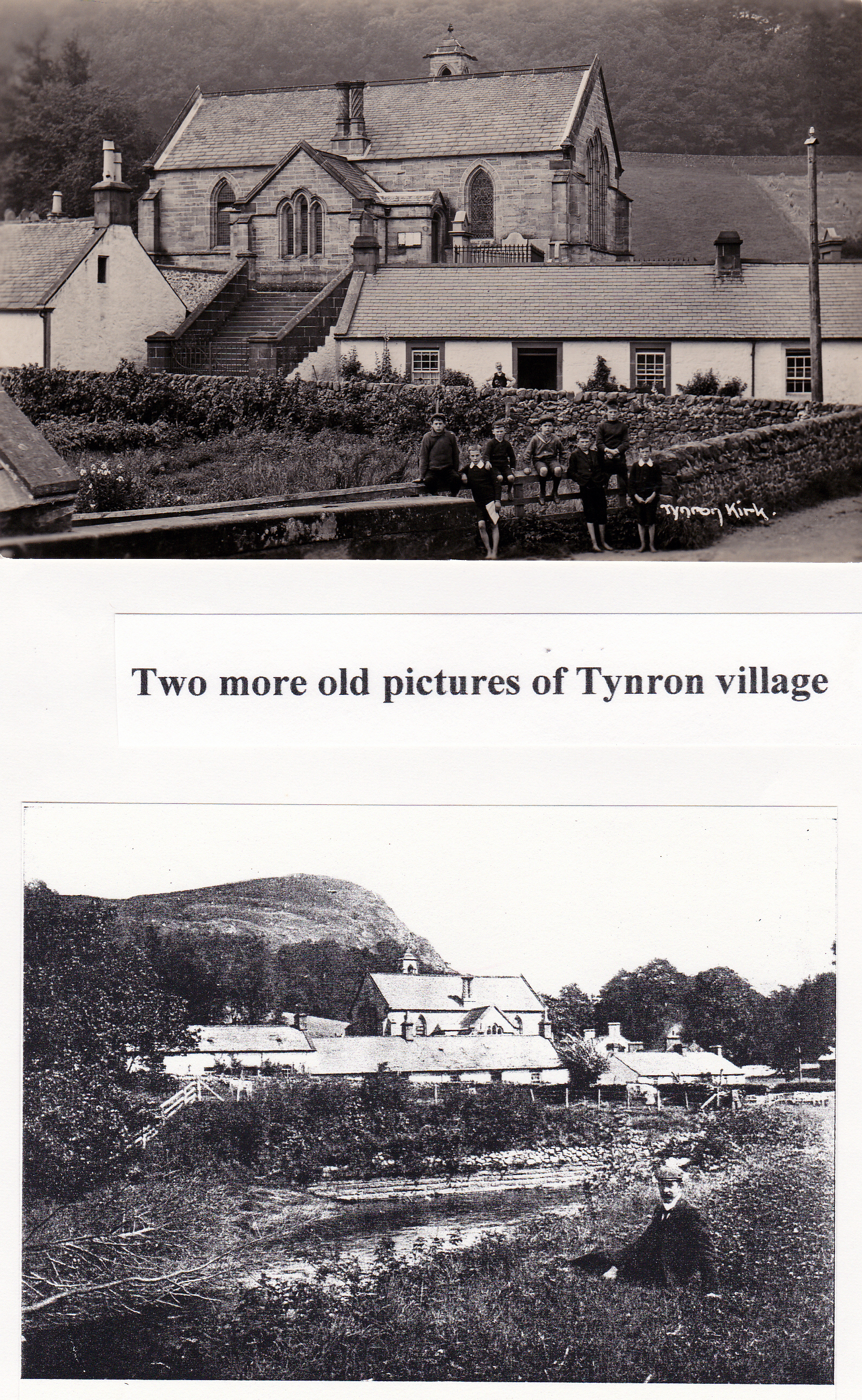

Jimmy Laurie from the shop sold his wares at all the glen’s farms and bartered produce too, using a horse and cart. He is pictured on the right of the old photo above in the shop doorway. His nephew, Willie Wilson, started as his apprentice then took over the lease of the shop in 1914. William Wilson died 18 April 1969. He had retired in 1959 after 61 years working for the post office. “W. A. Wilson” can still be read above the post office door. He was an elder for 40 years and was awarded the British Empire Medal for meritorious service in the Coronation Honours of 1953. The story goes that Wilson was such a skinflint that he did not go to the Palace to receive his award as it meant shutting the shop for the day.

Another tale says that he used to use yesterday’s papers to wrap up deliveries, but then charged his customer half-price for the paper! Wilson carried paraffin on his cart, the smell of which permeated everything else. Mr Maxwell of Kirkconnel can remember buying cigarettes and as change was paid by Wilson in matches, patiently counted out. Wilson was a well-loved character, about whom there is a fund of stories. He was the first to bring a tractor to Tynron in the first war. Owning a tractor, he then was classed as an agricultural contractor and thus exempt from the call-up!

When Wilson retired, his niece, Marion Pollock, kept the shop open for a while into the sixties, then just the post office into the seventies. In the latter years the shop did not have much stock. The post office building was empty for a few years, then sold by Miss MacRae to Kevin and Gill Bailey in 1982.

Stamp franked in Tynron

Jim Glencorse

Regarding the whisky and much else too, Jim Glencorse’s reminiscences of the glen this century are really worth reprinting from Matt Mundell’s article from the Standard May 1981:

The Glen of Change

Jim (85) recalls the drovers and the three bob local whisky!

Beside a spindly glen road, over which he long since walked his lambs and ewes to market and where he collected groceries from a packman’s cart, Jim Glencorse is again watching the start to one of the outbye world’s most critical seasons, the hill lambing.

The forthcoming weeks of struggle, as each dawn unveils its unpredictable menu of successes, disappointments, joys and sorrows to the region’s upland sheep men, will jog many memories for Jim, whose first steps in a lambing field were taken before the turn of the century.

In over 80 years of dwelling in the same quiet burnside Jim Glencorse has seen many changes in his home, Shinnel Glen. While progress has remoulded dramatically many south-west valleys through mechanisation, new farming techniques, stock intensification and improvement, timber encroachment, holiday homes and fewer herdings, Jim remembers clearly some of the bygone days’ colourful happenings around Tynron: The big droves of sheep coming over the hills from Lanark on their way to the Stewartry.

- His own days of droving to Thornhill, when the roads were dotted every 20 yards with flocks from surrounding glenways.

- Ploughing and drilling one day on the steep braes with Clydesdales and Half-Bred horses.

- The world-famed Tynron Kirk blended whisky.

- The weekly “mobile shop” – a horse and sheeted spring cart.

- The big “neighbourings” at the sheep clippings.

All these features have gone now. So too has Tynron Upper School, where Jim was a pupil until he left at 14 years of age to work on his father’s nearby Strathmilligan farm, where he had already been a big help at the lambing for several years prior to leaving the school desk.

“It was a big mistake when they started closing down these country schools. You could learn all you needed to know there,” said Jim, who recalls some pupils from the likes of outbye Shinnelhead at the head of the glen having to walk several miles daily to their one teacher school. “I have seen them weel drookit many a morning when they came in,” he said.

The Upper School is now a dwelling-house. All these youngsters would no doubt be from farming and shepherding families, but the takeover by forestry in these straths and the economic need to merge herdings has trimmed back considerably on glen folk employed in farming.

Several of the farms in these early days had as many as three shepherds. Strathmilligan, a 230 acre unit stocking five score of Blackface ewes and Ayrshire cows crossed with a Dairy Shorthorn bull, was always a family farm and Jim, who is 85 years old in July, has never lived beyond its sight. He himself took over the tenancy from his late father, John, in 1937 and retired into his home at Glenburn at the farm road end when well past the pension age.

Strathmilligan had also about 40 to 50 acres of arable ground and four or five acres were broken each year. Jim was still young when he started behind the Clydesdale horse and the swing plough. But for some of the other work, such as drilling, he preferred the Half-Bred horses. “They were smarter on their feet and easier kept and had an advantage with their smaller feet on top of the furrows.” The lea always had to be ploughed one way, down the steep hill, even with horses.

His recollections of what he admits were far happier days include his treks to Thornhill with the farm’s sheep. For a Saturday sale the stock was sometimes driven down the glen on a Friday and was put in a field overnight near Carronbridge. “You needed a good dog for that job and they got keen on this work.”

“We were lucky sometimes if we got as much as £1 for lambs,” says Jim. “There were some big sales though, probably as big as they are now.”

He can remember too the days his father walked calving heifers over to Moniaive station for entraining to sales at Castle Douglas. One nearby farmer, John Wallace of Macqueston, Jim recollects, cycled to Castle Douglas mart in the morning to buy heifer calves, cycled back home and then spent an hour or so sowing grain or working in the garden.

Jim’s own droving tramps to Thornhill took only a few hours. They were jovial days for the shepherds and farmers. “I have seen the road lined with stock as far as you could see, heading for the sales. Maybe a drove every 20 yards with folk from Moniaive and even Dalry travelling them.”

Prior to that there were the days when mighty droves of sheep passed the farm loaning on their way over the hill tracks from Lanark sales, heading to the Stewartry. There are still signs of the old pad coming over from Auchenhessnane past Pinzarie and Jim himself has taken stock on its continuation over from Birkhill to come out near Hastings Hall at Moniaive. “It was a well-worn road,” he said.

The mode of transport changed, but before the likes of Alex Wood started to haul stock in and out of the Penpont glens by cattle float, there was still the likes of grocer, Jimmy Laurie, from Tynron selling his wares weekly at all the glen’s farmsteads and cottages from his horse and cart. The only protection for the goods heaped in boxes on the spring cart, including far famed thick black tobacco, was a sheet. But Jimmy Laurie carted provisions up the water summer and winter.

He had another claim to fame for the whisky which he blended. Tynron Kirk Whisky was sent at one time to Australia, New Zealand and Canada. The old jars carrying the Tynron Kirk Whisky imprint are now collectors’ items, if you can find one. The 80 proof whisky sold at three shillings a 5 gill bottle and the 70 proof at 2s 6d. “I have heard some people say you only needed two halves. That was enough.”

The grocery business was taken over by William Wilson, who had worked for Laurie since he was a youngster and whose wage at one time was reported as being a pair of boots and a suit of clothes.

Jim Glencorse can still remember the first motor vehicle which came up the Shinnel. “Everybody was running to see it” His own method of travelling has changed little, for he still bikes to Tynron on a cycle he bought in the 1920s and which he has kept in good working order since.

For a hill farmer the vagaries of the weather can bring bitter recollections. Jim vividly recalls the 26th and 27th April 1919. “That was a bad storm, the worst. We were just in the middle of the lambing. The snow began at 11 o’clock and I thought it was just a shower, which would go past. But we could not see the dykes at night. There were lambs buried galore. They were all right if they were at the dykeback with some shelter.”

“Then 1947 was bad too. There were a terrible number of lambs lost that year. It rained for a whole week without stopping. The wind would have blown the coat off you. There were lambs lying in the morning on their backs with their bellies turned up and their mothers were away getting shelter. Where there were burns an awful lot of lambs were washed away.”

In the changing fortunes of the glen, Jim reckons the introduction of modern veterinary aids helped improve the sheep stock and led to higher lambing percentages. That and pasture improvement.

But it was always hard to make a profit, he contended. “I remember there used to be a lot of corn grown on the hills before my day. The ministers were paid with the crop, but if it was grown beyond the dyke the minister could not claim it.”

The social scene has changed too in Shinnel. Jim used to bowl at a house, long demolished, called Clodra, and here too they held many enjoyable invitation-only dances, some surviving from 7pm to 5am. He remembers walking back home from a dance once in Scaur Water and finding the family sitting at breakfast when he arrived back. He had then to change clothes and get onto the road and walk two heifers to Thornhill market. One did not make the required price, so he drove them home, where one promptly gave birth to twin calves.

There are plenty of reminiscences too about the sheep shearing. Jim was buister, the youngster who puts on the flock brand with Archangel tar, at many clippings even before leaving school. He has seen as many as 13 men clipping at the neighbourings, which brought together all the sheepmen from the glens.

“There were some happy days. Even the folk were different too somehow,” said Jim.

Glencorse is an old family name in Tynron, but now Jim has died and he was the last Glencorse in the glen. Browns of Macqueston and Telfers in Parkhouse are the main families with deep roots now in Tynron. The oldest inhabitant, until she moved in 1993, was 86 year old Miss Annie Watson of Stenhouse Lodge. Annie was born in the mining village of Kirkconnel and came to Killiewarren as a servant in 1919 straight out of school. In 1941 she moved to Stenhouse.

The first substantial buildings in Tynron after the school were in 1785 when Kirkland and its farmhouse were built and also the manse with its 14 acre glebe in 1786. The farmhouse is one of the few places with a date over the door. The kirk cottages would be of much the same age. They would have replaced the previous damp houses. The kirk cottages were rebuilt about 1860, when some houses were still thatched. Lann Hall was apparently built in 1745, making it the second oldest building in Tynron.