In 1072, only 6 years after Hastings, William the Conqueror invaded Scotland and the Scottish king, Malcolm III, became his vassal. Norman influences came in.

David I

David I, especially, (1124-53), encouraged Norman infiltration and, with it, feudalism. This was a great way of getting Scotland organised and it meant that the king finally had a way of ruling effectively over remote parts of his land, like Tynron.

The glen came under a large landowner, receiving land via the favour of the king, to whom all land ultimately belonged. The landowner had tenants who employed serfs, who became tied to the land.

In 1124 Nithsdale was one of the great feudal lordships. The lord’s name, the first local landowner’s name known, was Dunegal, who lived at Morton Castle. Morton Castle is a picturesque spot by a loch, hidden away at 890992. On Dunegal’s death this northern part of Nithsdale passed to Macdonald, his son.

Mottes

Mottes were thrown up around 1200 by incoming landlords, largely Anglo-Norman, in this “barbarous” area. Typical Scottish names like Fraser, Menzies and Balliol, Bruce, Comyn, Grant and Gourlay originate from these times. Curiously, no mottes exist in the glen, but Tynron Doon would have been used as one.

There are many nearby, the nearest just a few minutes away in Glencairn. The Pele Tower above Peelton at 800908 is now thickly planted with prickly forestry. There is a delightful wee motte at Maxwelton in the wood by the road at 817897. And there is a splendid motte by the Cairn Water at 799900, quaintly labelled as “mote and bow butts” on the 1st Series 1:25000 OS map.

The border of Tynron Glen and Glencairn has Shancastle Doon. “Sean chaisteal” means “old castle” in Gaelic and there was once a tower with massive walls on top of Shancastle, now thoroughly robbed for building at Maxwelton. Fascinatingly, Roy’s map of 1747 names this hill “Shanktourn”, indicating that there definitely was a tower.

Top of Shancastle looking down the glen with aerials to boost TV reception at The Ford with William Shaw

French was the language used by this new aristocracy, but it never got a general hold. Galloway, indeed, remained largely Gaelic-speaking, but over much of the country the Scots tongue, akin to English, had taken over by 1300.

Houses

Houses of the time would have been of unmortared stone or of turf, thatched with bracken, heather or broom. More prosperous people might have had wooden-framed houses with wattle and clay walls. Most houses had one room, no chimney, no light and no ventilation. Cattle were tethered in the house. Better-off tenants could have had two rooms with tiny windows. There was little point in building better anyway, because of unrest, Border raids and insecurity of tenure. People expected their dwellings to be knocked down during raids. Because of the materials used, traces of these early houses are hard to find, as once they fell down they would melt back into the land.

Death of Alexander III

A steady increase in population had led to the clearance and cultivation of more virgin and marginal land in the glen up to the climatic deterioration after 1300 with cooler summers and colder winters which must have dampened the ardour of the keenest of farmers. It is thought that a huge volcanic eruption of Hekla around 1300 darkened the skies and reduced sunlight, thus ruining crops. This was just one problem.

Alexander III’s death in 1286 left no heir to the Scottish throne. The ensuing disputes brought the end to many years of virtual peace and the beginning of centuries of unrest. Tynron could scarcely have escaped the Civil War of 1286-7 and the wars with England starting in 1296.

In 1300 Edward I invaded Galloway, as part of his takeover of the whole of Scotland.

Bruce

There followed in 1306 the notorious episode of Robert the Bruce (allegedly) slaying the Red Comyn in Dumfries, taking refuge in the castle of Tynron Doon and receiving porridge from the good lady of Cairneycroft.

By 1307 the glen must have been one of the routes used by men of Robert Bruce dealing with the opposition of the family of the Comyn and John Balliol, his rival for the throne, who was based in Galloway. Tynron must have seen much activity at this time. Galloway even applied to the English king (Edward II by this time) for help, but was taken under control by Robert in 1308 and ravaged.

Tibbers and Dalswinton castles remained English strongholds and were not taken until 1313. In 1313 Bruce also took Dumfries Castle and sealed his grip on Galloway. However, the English were soon back in the Tynron area, followed by the first great plague of 1349-50. Tynron must have suffered raids in the fourteenth century, as the English tried to take over Southern Scotland and were alternately repulsed and half-successful. Poorer climate, wars and plagues must have reduced the population considerably and made the fourteenth century much tougher than the prosperous thirteenth.

Tibbers Castle

Tibbers Castle 862982 is well worth a visit. With its still considerable moss-covered walls, it is a creepy, magical place, strewn with pink purslane in summer. It is sited on the tip of a flat-topped basalt ridge and is perched above the Nith. The walls are surrounded by a deep ditch and there is a large bailey. It was one of the Norman mottes until the castle was built from 1298. Edward I was there in 1298 after the Battle of Falkirk, presumably supervising the construction. Tibbers Castle had a short life, being dismantled under the orders of Robert the Bruce after Bannockburn in order to prevent the English reusing it.

Landowners

In 1309, a descendant of Dunegal, Thomas Randolph, who married Robert’s sister, was lord of Nithsdale. This demonstrates that land could only be held by those loyal to the king, like Thomas Randolph, who had to choose sides carefully. The following pages mention some of the large landowners of Tynron over the centuries.

The Douglases

In 1354 the Barony of Drumlanrig, formerly an outlying territory of the Earls of Mar in Aberdeenshire, was bestowed on the Douglas family by David II, including the lands of Pinzarie and Bennan. The Douglases, however, had been at Drumlanrig as early as 1170.

Galloway was still very much a separate nationalistic entity even in 1369, mainly Gaelic-speaking and distinct from Scotland proper, when the whole of Eastern Galloway between the Cree and the Nith, largely English-speaking, was bestowed on Archibald Douglas (The Grim). He reunited Galloway, of which Tynron was part, under the Black Douglases. In the 1360s the Tibbers and Morton baronies passed to the Douglas family through marriage and lineage.

The Douglases thus became very powerful and that was their undoing. In 1455 James II put down the Black Douglases and disowned them forever, so Galloway lost its semi-independence for ever. James II created his alternative aristocracy when Lord Dalkeith became Earl of Morton. Local Douglas family power waned when they got into debt after 1657, but they still nevertheless somehow retained the lands of Tynron until they sold up in 1727. See the Hearth Tax of 1691 below.

Killiewarren

To me Killiewarren is the most interesting building in the glen and not just because it is the oldest (1617). It was originally a three-storied fortified house, Stenhouse Castle?, with tremendously thick walls. An arched gateway was demolished in the early 1800s.

The Douglases evidently needed some protection, especially in Covenanting times, when they were on the side of the persecutors. This is how Nigel Tranter describes Killiewarren in “The Fortified House in Scotland”:

Pleasantly situated in wooded foothill country a mile north-west of Tynron, this is a small laird’s house of the early 17th century, plain and sturdy. It is oblong on plan and three storeys in height, the roof appears to have been altered, as so frequently occurs. As also is typical, most windows have been enlarged and some built up. A more modern wing of two storeys has been erected to the west, and in the south front of this lies the present main door. Over this doorway two panels have been inserted, no doubt removed from over the original door which is on the other, or north, side of the house now obscured by modern work. The panels, now pleasingly coloured, bear the arms of Douglas and the initials I.D. and F.D., with the date 1617. The early doorway is arched, with moulded surround.

Internally the house has been completely modernised, no features of interest remaining. There is no vaulting, and one or two of the corbels for the support of the first floor is still to be seen at the kitchen ceiling. The usual arrangement of Hall on the first floor and bedroom accommodation above would prevail. There is now no stair within the old portion of the house, but the original turnpike would appear to have risen in the north-east angle, to the left of the old doorway. The building is in good repair and is now occupied as a farmhouse, whitewashed and trim.

Long Distance View of Killiewarren

The Queensberry Papers

The Queensberry Papers outline the acquisition of lands in Tynron. For example, in 1509 the lands of Schynell Croft are mentioned. 1606 saw the acquisition by Queensberry of Achinbrack, Mid-Schynelhead, Killiewarren, Benan, Denary (Pinzarie) and Craigencoon from Maitland of Auchingassel, Penpont, part of the Barony of Tibbers. In 1686 Queensberry Estate bought the manor and pertinents of Douglas of Stenhouse.

In 1511 the Barony of Glencairn had been granted by James IV to the Cunninghams and included, as well as land in Glencairn, Cormyligane, Corrochdow, Kirkconnell, Croglinmark, Questoune, Lawne, Stanhouse, Kristemark, Margmalloch, Tanelagoch, Mirgwastune and Mirgmalloch, in other words and other spellings the land to the south-west of the Shinnel, which was mostly in hands other than Queensberry’s over the centuries.

It seems to me very difficult to keep track of exactly who owned what and when, as great chunks of Tynron were transferred from one large landowner to another. “The History of the Douglas Family” by Adams mentions lots of this dealing and includes an interesting snippet about William Douglas of Baitford (Penpont), tried for killing James Douglas of Killevarren in 1603. He was convicted of other crimes in 1610, sentenced to be hung, but somehow cheated the gibbet and still owned the Kirklands of Tynron in 1660/8. This is typical of feuds amongst the large families of the area.

The Wilsons of Croglin

During the fifteenth century the Wilsons of Croglin, living in Macqueston, had acquired all the land south-west of the Shinnel, with the local Douglases based at Stenhouse, having all the land to the north-east.

The failure of the Ayr Douglas Bank in 1781 ruined the Wilsons, who had been a powerful family, owning by 1796, when the estate was finally sold, Appine, Margmalloch, Croglin, Tinlego, Marqueston Park, Kirkconnell, Birkhill and Land. The main branch of the Wilsons moved to Ulster. All the Wilsons did not leave, as the 1827 Valuation still shows Francis Wilson of Croglin with his holdings up the glen and Tynron’s ministers were Wilsons until 1870.

The site of Croglin itself is now marked by a small unplanted L-shaped pile of stones 40 metres into the sitkas by the main forestry road at 743984. It was abandoned soon after 1805. For more information see TDGNHAS 1949-50 “Wilson of Croglin”.

The Lag Charters

“The Lag Charters” record the details of the Grierson family in Tynron. We know that John Grierson was in Cormilligane in 1535 and owned Carrochdow and Murmulzoth. In 1545 he still owned the same, though the latter is now spelt Muirmolloch (near Kirkconnel?). The Griersons had Capenoch in 1607. The earliest local record is circa 1418 when George de Dunbarre gave up his lands at Le Ard (the Barony of) and Tynnroun to Gilbert Grierson.

Maps and tax returns

These old documents mentioned so far are a very valuable source of information, but it is bitty as far as Tynron is concerned. Written history takes a great leap forward with the publication of the first maps, tax returns and valuations.

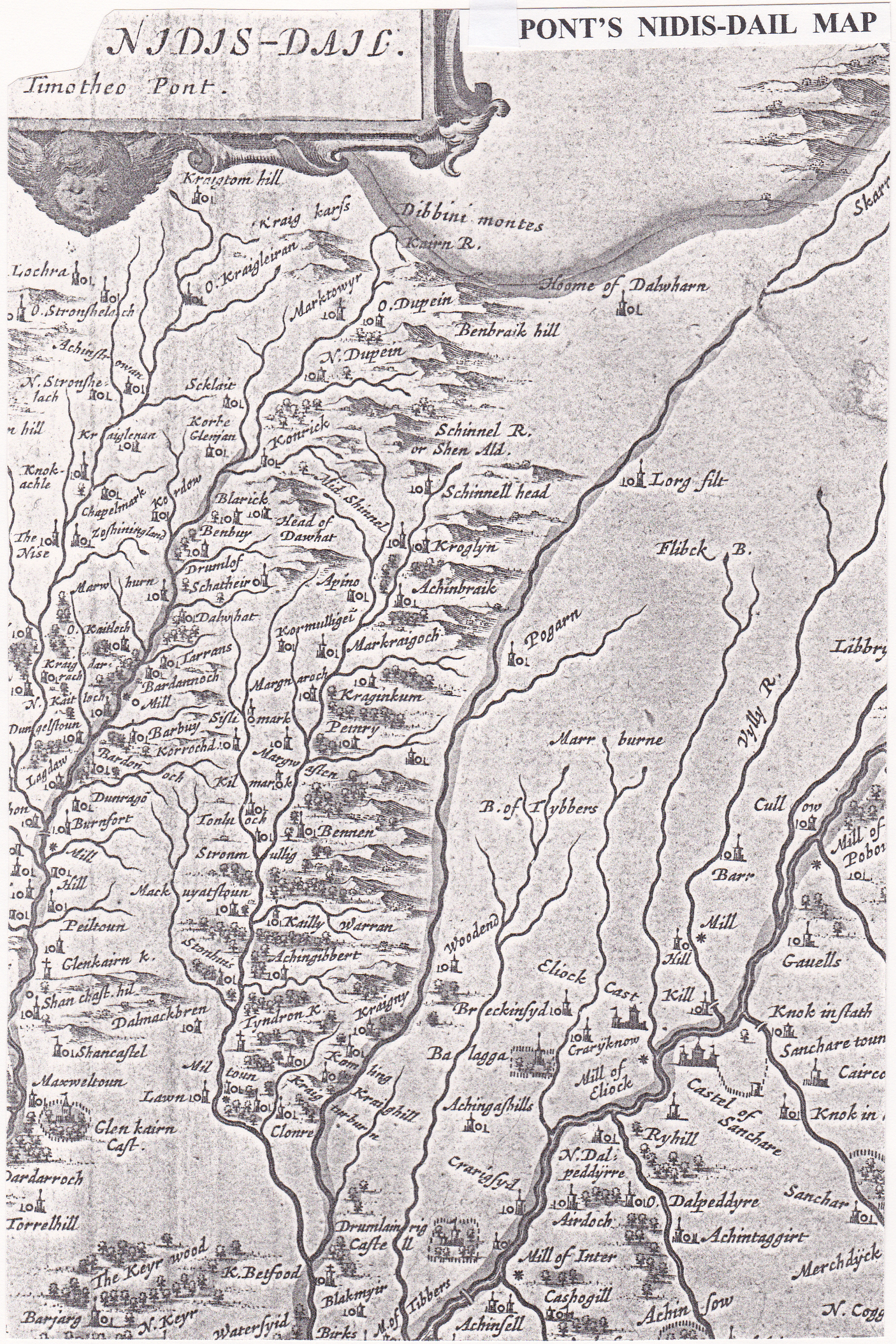

Nidisdail Map

Timothy Pont was a Gaelic speaker and a wonderful innovative map-maker, mapping the whole of Scotland on foot. He drew the first surviving reasonably accurate map of Nithsdale circa 1583-96, map, but it was not published until 1654 in Blaeu’s Atlas. This is an enormously rich source of information about Scotland 400 hundred years ago.

Place names may not always be accurately marked and not every place was shown perhaps. The Shinnel Glen is full of names, for example, while the Scaur is surprisingly empty of detail. But what an extremely precious record of the Shinnel Glen and an excellent illustration of the fact that a map is worth a thousand words.

To show how much ahead of his time Pont was, a 1725 map of Nithisdale by the geographer, Herman Moll, only marks Shinnel River, Ahinbrach Hill and Sislemark: an interesting selection, as Moll claimed his new and correct maps of Scotland were a “work long wanted and very useful for all gentlemen that travel to any part of that kingdom”.

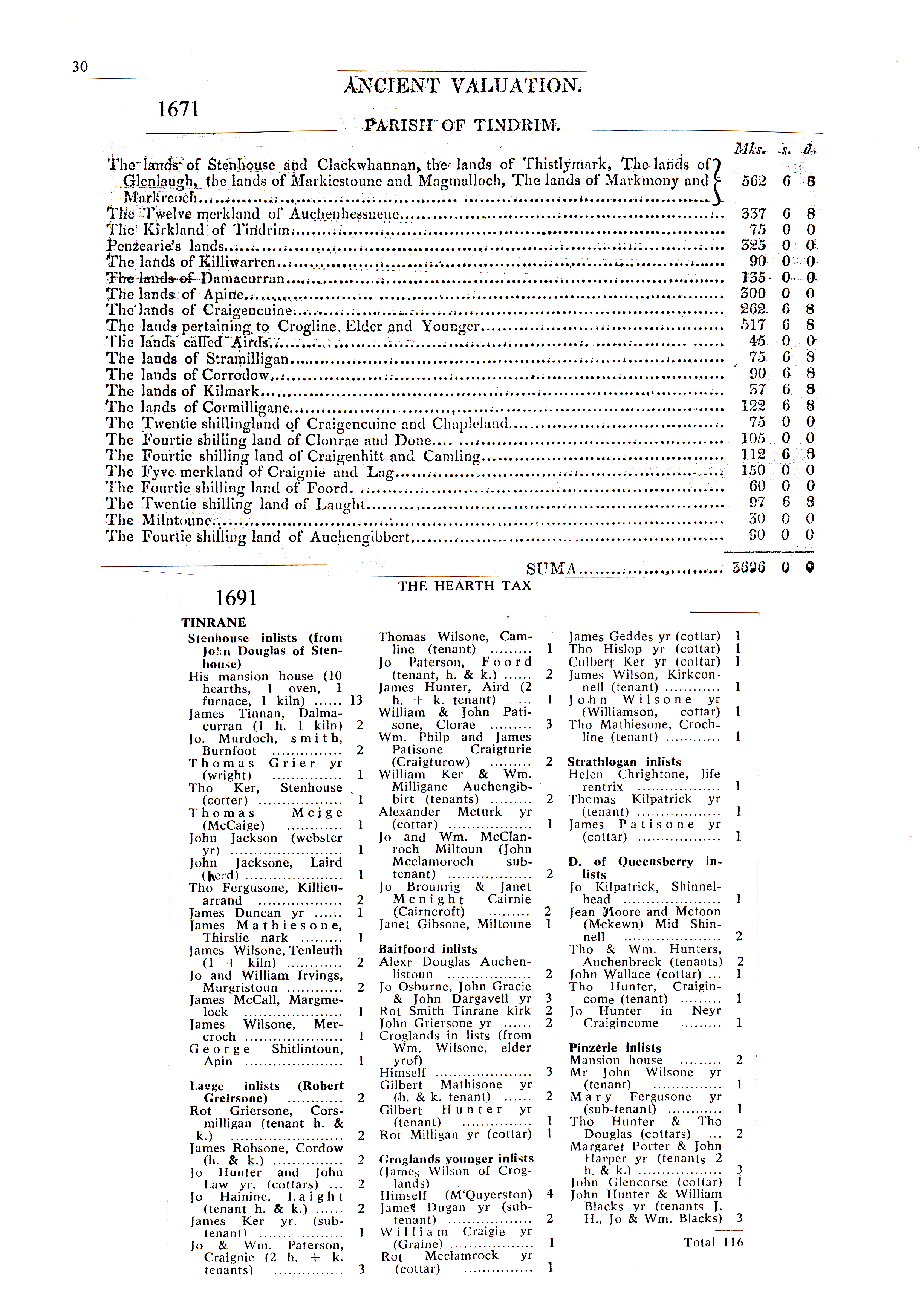

Valuation and Hearth Tax

However, sometimes words are worth a very great deal. Witness the importance of the 1671 Valuation and the Hearth Tax of 1691. Remember that these were compiled at a time of great unrest in Scotland and pretty poor climate too.

The valuation interestingly fails to include Auchenbrack, perhaps deliberately in order to avoid payment! Auchenbrack is part of the Queensberry estate for the hearth tax however. It is fascinating comparing the Valuation and Hearth Taxes, just twenty years or so apart and seeing how land changed hands regularly. The names of the properties, though, are all familiar and this shows how the present pattern was ingrained 300 years ago.

The hearth tax list was compiled to raise money for armies fighting against the Jacobites. Duncan Adamson presented it in TDGNHAS 1970.

The Heidless Horseman o’ Tynron Doon

I thought long and hard about including superstitions, hobgoblins, fairies and druids in this epic, but I finally succumbed to mentioning this traditional Tynron story.

McMilligan from Dalgarnock was visiting a lass in Tynron Castle. One of her brothers was not too pleased to find them together in a compromising position. McMilligan leapt onto his horse and straight over the edge in the dark. He landed at the foot of Tynron Doon craig. The force knocked off his head, which rolled down the hill into St Bride’s Well at Clonrae. No longer possessing his head, he could not go to heaven, even though he was a god-fearing man. So now he can oft be seen on his nag along the road between the Doon and Dalgarnock, near Thornhill.

Trotter has more about the heidless horseman in Gallovidian magazine, winter 1902.