In 1700 the view of Tynron Glen was of an open, undrained, virtually treeless landscape with infertile moor and bog, mud tracks, meagre crops of oats and bere, many an irregular patch of arable land on the valley sides, ill-bred, half-starved cattle, oxen, sheep & pigs, hovels to live in and POVERTY.

Stagnation or decline were the only alternatives with the run-rig system, but the eighteenth century changed all that. Acts as early as 1661 to 1695 tried to change the face of farming through modernisation, but it was decades before they took effect locally. These acts allowed landlords to sweep away open run-rig fields and to enclose and rearrange the lands as they pleased. Thus began the change which made the glen look very much like it does today.

The first half of the eighteenth century saw a continuation of national unrest with its local repercussions. The Act of Union of 1707 caused much unrest before and after, notably amongst the locally strong Cameronians, the extreme Covenanters. The rebellions of 1715 and 1745 meant the raising of volunteer forces from Tynron and consequent local turmoil, especially when the Highland army were in Dumfries and Thornhill. Bonnie Prince Charlie was possibly in Tynron in 1745. His sick and wounded men were treated by Dr John Trotter in the long-gone Burnfoot, by Dalmakerran. Recruits from Tynron may have fought against the Americans in the 1770s or against France in the 1790s.

In 1747 Rev Peter Rae made an important handwritten manuscript concerning Tynron, giving us a description of the parish. His original work and a transcript are in the Ewart.

Changes in Life

Life was changing fast in the later years of the century. Tea came in the 1760s, sugar and coffee in the 1780s and with the sugar a boom in jam and jelly making. Currants and berries were cultivated in back yards. For the educated, newspapers came from Glasgow and London to give Tynronians their first wider view of the world. Many folk now had watches and clocks, cotton clothes and drank whisky. However, rheumatism, asthma and smallpox still were prevalent and accounted for many deaths.

Enclosure and Stone Dykes

Enclosure brought the first major rural upheaval since the Normans instituted the feudal system. The boundaries of the fields were set by drystane dykes. Run-rig was cast aside.

One most interesting question is when enclosures came to the Shinnel Glen. Some people seem to think that they have always been there, but the following gives some idea of when they were built.

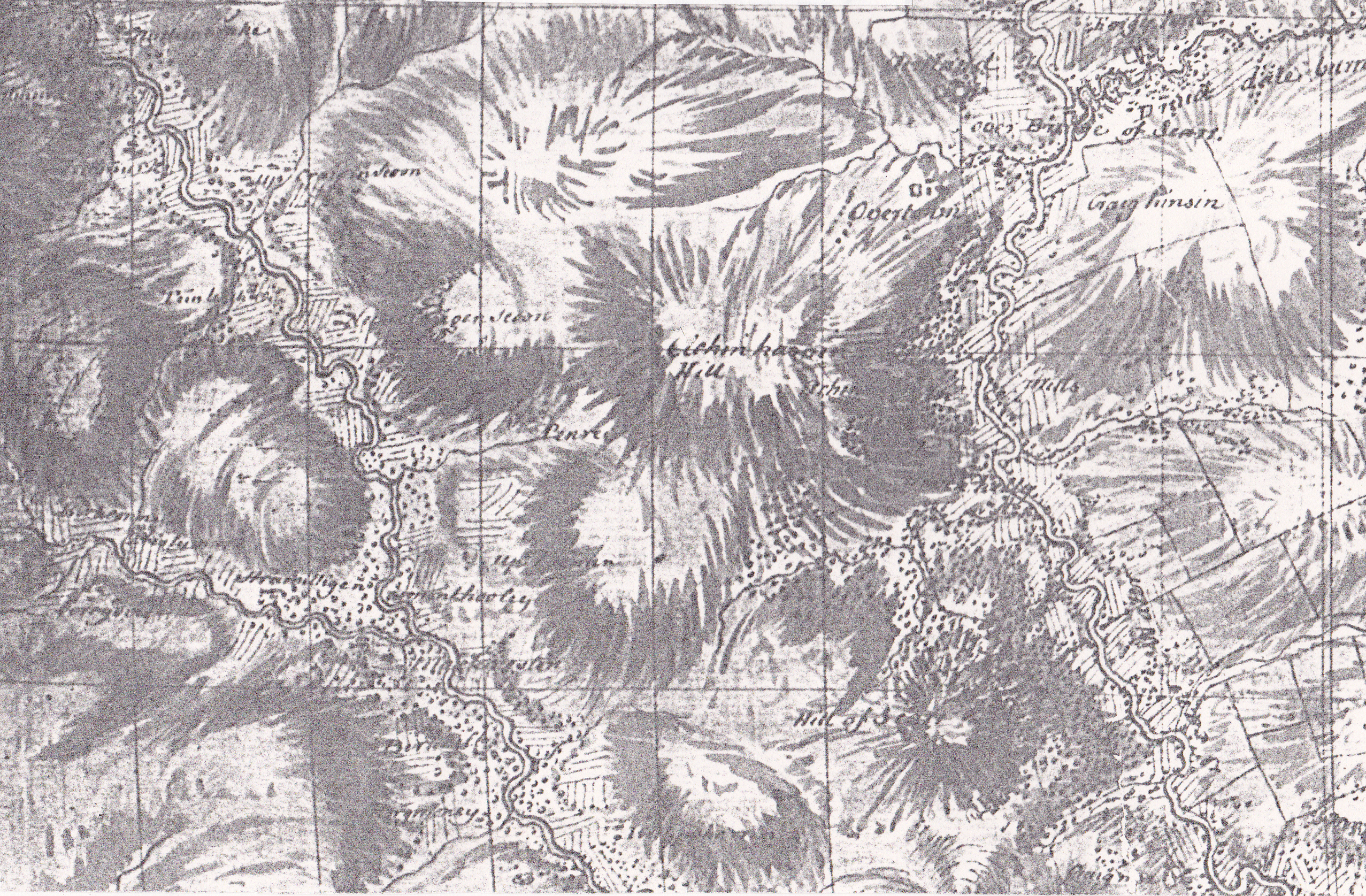

Roy’s Map

General Roy produced maps for military use. It is difficult to read some of the place names, but the hill shading is effective and cultivated areas are shown. Roy’s map of 1747 shows that there were already enclosures up the Scaur on the right side of the map, but none are marked up the Shinnel, also on Queensberry land. Some parts of Galloway even had enclosures in the 1730s. Remember the Levellers?

The Queensberry estate maps of Tynron of 1772 show no stone dykes. Durisdeer parish, owned by Queensberry, was still unenclosed in the 1790s. Neither, most significantly, is there mention of enclosure in the 1790s Statistical Account for Tynron. Such a radical change would surely have been recorded. Yet in Penpont in the 1790s “there are many inclosures: and the disposition to inclose seems to increase”.

Much of the Shinnel Glen was not enclosed until some time into the nineteenth century. 1800 – 1820 seems likely to have been the time when most of Tynron’s dykes were built. Dykes were certainly being built at Cairneycroft in 1804 and Singer’s evidence supports this too (see later).

A number of people must have been evicted, as the small, scattered holdings were swept into large compact units. Dykes brought planning and order. On a particular piece of land one tenant took over the running, instead of the former communal efforts on the rigs.

No longer were the peasants tied to their rigs. Some people had to move into Tynron village and all the common pasture was lost in the glen as landlords put in more sheep and introduced black cattle for selling in England.

The Lann estate map of 1834, kept at Capenoch, shows that dyking was completed by then. Lann had the wonderful gateposts built along the road, which are unusual, but not unique to Tynron. In 1996 Six pairs of stone gateposts remain plus four singles. The gateways are too narrow for modern machinery, so some have been removed. It was sad that another of these bit the dust in the eighties, as they are attractive features. Two pairs of gateposts no longer even have a gateway. In 1871 George Black, aged seven, climbed a pillar at Lann Hall and the top stone gave way, falling on the boy and crushing him to death.

Lann Hall gateposts with Tynron Doon in the background

Dykes were built in the summer months by whole families, male and female, old and young. Stones were gathered, or rock quarried, then hauled on slypes (sleds). In winter months, stones were collected or quarried and dumped in convenient spots. March dykes were Galloway dykes built to five feet, but the subdivision dykes were smaller. Some have lasted well and are still in excellent condition after 200 years, but unfortunately others have fallen into disuse, been removed or replaced by fences. It is labour intensive and thus expensive to repair stone dykes and, while some are conscientiously repaired, others are botched, gaps filled with wood, old gates or corrugated iron sheets. A favourite and all too widespread solution in the 1990s is to put up a single or double strand of barbed wire or electric fence on top of the dyke.

Tynron’s Farming Revolution

Apart from legislation, other factors provided simultaneous stimuli. In the eighteenth century new ideas and new crops, new thoughts on stock-breeding filtered northwards from England. This was a bonus of the 1707 Union of Scotland and England. Many Scots now travelled south and saw improved agriculture and brought back and spread new ideas.

Larger stone houses were built for the tenants by Queensberry. The gentry could afford to build houses fit for their position: Lann Hall, Stenhouse, Kirkland.

Selected tenants were given longer leases, giving them more incentive to farm well.

Drainage, liming and rotation were brought in. Lime itself revolutionised farming in Tynron and was brought from Closeburn and Barjarg from 1774. Extensive underground chambers were quarried out of the Barjarg Carboniferous limestone in the woods at 882903. In 1805 Tynron was the leading destination for Barjarg lime, when 4761 measures were carted to Tynron.

Turnips were also a godsend, reaching Tynron perhaps as early as 1745 and later, possibly in the 1770s, the advent of potatoes put an end to famine in most years. Fields were now kept specially for hay. Beans and peas improved fertility. Turnips and hay and improved pasture land meant that more animals were kept over winter and more dung produced. Turnips and potatoes were also important as cleaning crops instead of fallow in the new rotations (mentioned later). Trees were planted for shelter and land improvement.

The building of the dykes meant the removal of most of the surface stones on the fields. The unprofitable outfield was replaced by seasonal pastures. Improved Scots ploughs were lighter and required only one man and two horses, or four on heavy ground. New fields were broken in, increasing crops after 1750. After about 1770 the new ploughs straightened out the old rigs.

Urban growth in Glasgow and Dumfries together with an increasing English market boosted agriculture and encouraged production of a surplus to sell instead of mere subsistence.

Wages increased – £8 per annum for a farm labourer in 1790. Diet was better, so health improved. All this meant a revolution in Tynron’s agriculture and greater prosperity in some measure to everybody, though not overnight. Changes were very slow, but a comparison of farming in 1700 with that of 1800 shows a tremendous difference.

The First Statistical Account

To know what the glen was like at the end of the century, there is the first really useful description of Tynron Parish in 1791-3 in the Statistical Account. Here the Rev James Wilson reports on his parish. He thought TYNRON had been the spelling since 1730.

He described green hills, well clothed with grass, feeding 8,000 Blackface sheep. They gave shaggy wool of poor quality, sold in the Borders and Cumberland. Crops were still neither luxurious nor early. Oats was the main crop, and, with potatoes, provided half the food of the common people. Farms with only sheep in 1750 now had black cattle on their lowest land.

Penpont Parish had barley, wheat, turnips, clover and rye-grass. Thornhill (Morton) also had lint and peas. Low Lann has a field called Wheat Park on the 1834 estate map, though it was rather optimistic to try and grow wheat in the glen. The enlarged tillage area meant more labourers were needed, the population was rising and new houses were built.

Farms were now let by the Duke of Queensberry for 19 years at moderate rates. He had eleven separate farms and half the parish was on the Queensberry Estate. Some Queensberry tenants with 19 year leases actually put up dykes at their own expense.

Peat was commonly used at the upper end of the glen until the late nineteenth century, though it was easier in Tynron and the lower end of the glen to get coal from Sanquhar.

The rotation used in the glen was:-

| Year 1 | Lime the land while in pasture | | Year 2 | Pasture, ploughed in autumn | | Year 3 | Oats | | Year 4 | Oats | | Year 5 | Potatoes or turnips | | Year 6 | Barley undersown with grass |

Diary of Andrew Hunter

Surgeon of Camling, Tynron 1781

This diary, available in the Ewart Library, is absolutely fascinating. While not playing cards, shooting pistols or bleeding people, Hunter wrote in his diary. These are some of the things he wrote about farm activities:

| April | The people are employed ploughing the potato land. Loading dung. Building dykes. Setting potatoes. | | May | Casting peats at Thornhill Moss. Lot of rain throughout summer.| | August | Reaping oats. Shearing. | | September | Threshing. Making up the Millar of corn (Cairn Mill). Drying corn. Grinding corn. | | October | Lifting potatoes. Selling old & young beasts & stirks. | | November and December | Ploughing. Loading timber from the hill. |

From the beginning of the nineteenth century another extremely informative document is available to give us a clear picture of the situation in Tynron:

General View of the Agriculture, State of Property and Improvements in the County of Dumfries by Dr Singer 1812

Houses

Houses were not now covered in turf and straw or heather or ferns. Most people were anxious for the security of slate roofs. The Duke of Buccleuch “allowed” wood, slate and lime but tenants had to cart it themselves and fit it to the buildings. Buccleuch houses were the best kept in the country. The new farm buildings had the square layout with the farmhouse on the south side.

Implements

The new form of the Scots plough was gradually replaced by Small’s plough using two or three horses on a long rein. Light carts were pulled by one horse.

Slypes were still used on steep ground. There were threshing and winnowing machines, worked by water if possible or, if not, by horses, but no reaping machines yet.

Enclosures

There were quite a few in Tynron by 1812. The building of stone dykes on the sheep-walks was in full flow. Tenants on Queensberry’s 19 year lease put up the dykes at their own expense. There were no more commons in Tynron.

The earth dykes were hardly an efficient fence. Their height was usually 5 feet. In 1812 many of these sod dykes, having mouldered down, still disfigured some of the sheep-walks and required to be entirely levelled or removed. All earth dykes ought to be secured with a paling of wood on top.

Farming

The rotation included oats, barley, pease, turnips, potatoes and carrots (although there was trouble with the fly). There were a few patches of flax. Most farmers’ gardens had early potatoes, carrots, greens, peas, cabbage, beans, currants and gooseberries. The Tynron rotation now included a crop of hay taken in the seventh year.

Oxen were scarcely used by 1812, though highly recommended by Dr Singer, as cheaper, docile, powerful and steady. They also provided good meat and valuable skin. The great advantage of the horse was speed, important in beating the weather.

Sheep were all short Blackface despite Cheviots coming in.

Cows were mainly Galloway, a few Ayrshire.

Farmers knew about the importance of drainage but did little about it. However, the Shinnel was straightened using much labour and money.

Servants

Servants were hired for six months at hiring fairs, but it was better to have married servants in a cottage.

Peat

Each cottager’s fire needed 24 to 30 cartloads per annum.

Trees

There was a shortage in Tynron, very few pine, oak, ash, elm. More trees should be planted, but many were still being cut down. (Many were going to the expanding mining industry.) Tynron has natural oak, ash, birch & alder up to 25 years old. There were a few plantations of larch and Scots pine. The implication is that there were even fewer trees before 1780.